EECS 280 Tutorials

Assertions Guide

Assertions are a preemptive debugging tool. Add them to your code to detect bugs before they cause difficult-to-debug problems later in your code.

Using Assertions

The <cassert> header defines an assert() macro that checks a boolean condition:

- If the condition is true, nothing happens.

- If the condition is false, the program crashes immediately.

For example:

// primer-spec-highlight-start

#include <cassert>

// primer-spec-highlight-end

int main() {

int x = 2;

int y = 5;

// primer-spec-highlight-start

assert(x + 3 == y); // true, all good :)

assert(x > y); // false, crash!! (╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

// primer-spec-highlight-end

}

We might see this output when running the above:

test.exe: test.cpp:7: int main(): Assertion `x > y' failed.

Aborted

For debugging purposes, we use assert() to verify our program is behaving as intended and “fail fast” otherwise so that we can get to fixing the bug.

Assertions are intended for debugging, but you don’t have manually remove them before shipping production code. They can be turned off automatically by compiling with the -DNDEBUG flag.

Sanity Check

You might run into situations in your code where you think “this could never happen” - and you’re often right, unless there’s a bug somewhere! Adding assertions to “prevent the impossible” will expose such bugs.

For example, you might find that certain paths through the code are unreachable if everything is working as expected, and you can encode this as an assertion. Here’s an example, pulled from the project 3 specification.

Player * Player_factory(const std::string &name,

const std::string &strategy) {

// We need to check the value of strategy and return

// the corresponding player type.

if (strategy == "Simple") {

// The "new" keyword dynamically allocates an object.

return new SimplePlayer(name);

}

// Repeat for each other type of Player

...

// primer-spec-highlight-start

// Assuming we've checked for each kind of Player

// above, the code should never get here. If we do...

// something is very wrong and the assert lets us know!

assert(false);

// primer-spec-highlight-end

}

The assert(false) here is also helpful to suppress a warning the

compiler might otherwise give because it’s worried our code could reach

the end of the function without returning anything (g++ phrases this as “warning: control reaches end of non-void function”). But, with the assertion,

the end of the function can literally never be reached and the compiler

doesn’t give that warning.

Or, you might write code to ensure some property, like forcing a user to enter a non-negative number. You could add an assertion to verify the code has actually achieved that. Consider this example code:

int get_order_quantity() {

cout << "How many items would you like to order?" << endl;

// Get user input

int quantity;

cin >> quantity;

// Prompt them again if the input was invalid

if (quantity < 0) {

cout << "Invalid input. Please enter a non-negative number." << endl;

cin >> quantity;

}

// primer-spec-highlight-start

// We should have a valid quantity after the user interaction above.

// (Unless there's a bug somewhere - this will sanity check!)

assert(quantity >= 0);

// primer-spec-highlight-end

return quantity;

}

That assertion proves worthwhile, since there is a bug in the code! Because

the if statement only checks the first input for validity, an invalid

negative input for the second cin >> quantity could sneak through. But,

it would be immediately caught by the assertion and is easily debugged.

Verify Preconditions

Use assertions to verify the REQUIRES clause for each

function whenever possible. These are the preconditions that are required

for the function to have a chance of working correctly, so verifying them

up front is a good idea.

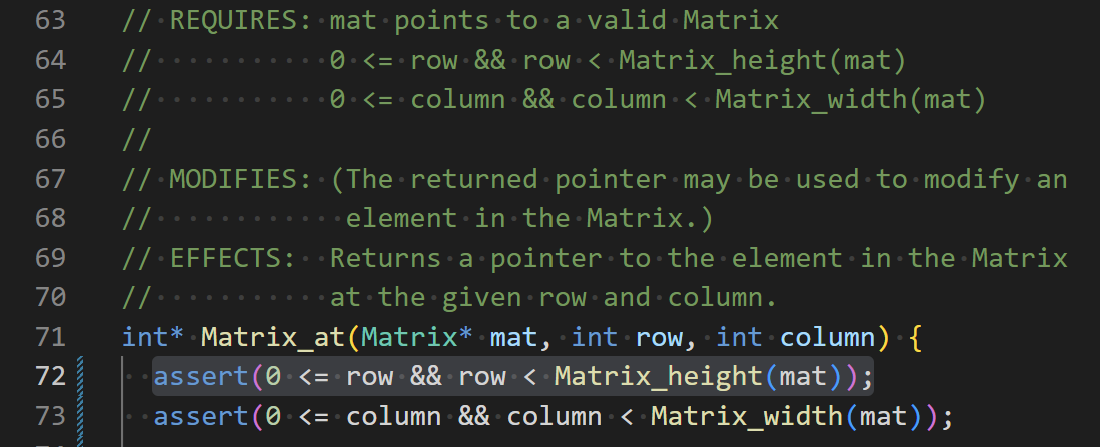

Example: Matrix_at() Preconditions

Here’s an example of assertions you could use in function that

provides access to data at a given row/column within a Matrix struct:

// primer-spec-highlight-start

// REQUIRES: mat points to a valid Matrix

// 0 <= row && row < Matrix_height(mat)

// 0 <= column && column < Matrix_width(mat)

// primer-spec-highlight-end

// EFFECTS: Returns a pointer to the element in

// the Matrix at the given row and column.

int* Matrix_at(Matrix* mat, int row, int column) {

// primer-spec-highlight-start

assert(0 <= row && row < mat->height);

assert(0 <= column && column < mat->width);

// primer-spec-highlight-end

// Implementation

// ...

}

If we were to call Matrix_at() with parameters that are outside the

bounds of the Matrix, we get a failed assert right away and can debug

the issue. These assertions are also invaluable while debugging other code

that uses Matrix_at() - if the assertions aren’t failing, you can safely

rule out any out-of-bounds bugs and focus your attention elsewhere.

Of course, you can’t assert every single thing in every REQUIRES clause.

Some of them can’t possibly be checked. Here’s another example:

// REQUIRES: mat points to a valid Matrix

// primer-spec-highlight-start

// the destination array is large enough

// primer-spec-highlight-end

// EFFECTS: Copies all data from the matrix to

// the given destination array

void copy_matrix_to_array(const Matrix* mat, int dest[]) {

// primer-spec-highlight-start

// Verify REQUIRES clause???

// primer-spec-highlight-end

// Implementation

// ...

}

In this case, we can’t use an assert to verify that the destination

array is large enough, because the int[] array parameter decays to

an int * type that doesn’t contain information about the size of

the original array.

Check Invariants

The representation invariants of an abstract data type (ADT) express the

conditions required for its present state to be valid. In other words,

do the member variables of a given struct or class object make sense

in terms of what it’s trying to represent? For example, Some examples:

- In a

Matrixstruct, thewidthandheightmembers should be positive numbers - In a Euchre

Cardclass, thesuitmember must be"spades","hearts","diamonds", or"clubs"

We try to write code carefully so that the representation invariants are set up correctly when an ADT object is created and preserved throughout any operations on it. And we’ll also rely on assuming they are true when we write code to work with the object. We can add assertions to verify those assumptions and fail fast if they’re ever broken.

Example: Matrix ADT

In a C-style ADT implemented with a struct, you can create a general helper to check invariants. For example, consider a Matrix ADT and a corresponding function to check its invariants:

struct Matrix {

int width;

int height;

int data[MAX_MATRIX_WIDTH * MAX_MATRIX_HEIGHT];

};

// EFFECTS: Uses assertions to verify the representation invariants

// for the given Matrix.

void Matrix_check_invariants(const Matrix* mat) {

assert(mat); // Shouldn't be nullptr

assert(0 < mat->width && mat->width <= MAX_MATRIX_WIDTH);

assert(0 < mat->height && mat->height <= MAX_MATRIX_HEIGHT);

}

Then, call it at as needed to proactively sanity check:

// REQUIRES: mat points to a valid Matrix

// EFFECTS: Returns a pointer to the last element (at the

// highest possible row/column) in the Matrix.

int * Matrix_last(Matrix* mat) {

// primer-spec-highlight-start

Matrix_check_invariants(mat);

// primer-spec-highlight-end

return &mat->data[mat->height * mat->width - 1];

}

In the example above, you could think of this as a check on the REQUIRES

clause that specifies mat must point to a valid Matrix. This keeps

us from wasting time if, for example, Matrix_last() appears to be broken

but the problem was really that we forgot to call Matrix_init() previously.

Example: List ADT

In a C++ style class, implement check_invariants() as a private member function. Call it after initializing member variables in the constructor and any time you make changes to your data representation (i.e. the member variables).

Here’s an example for a complex data structure called a linked list, in which individual nodes store data and connect to their neighbors via pointers:

class List {

private:

// Lists contain nodes, connected in a chain using pointers

struct Node {

Node *next;

Node *prev;

int datum;

};

// Member variables

Node *first;

Node *last;

int num_nodes;

// primer-spec-highlight-start

// Check represenation invariants with assert

void check_invariants() {

// Either it's empty with null first/last pointers,

// or it's not empty and neither should be null

assert(!first && !last || first && last);

// There's nothing before the first node

// and nothing after the last node.

assert(first->prev == nullptr);

assert(last->next == nullptr);

// Manually counting the number of nodes matches

// the number we're tracking in num_nodes

int count = 0;

for(Node *n = first; n; n = n->next) {

++count;

}

assert(count == num_nodes);

}

// primer-spec-highlight-end

public:

// Default constructor. Creates an empty list.

List : first(nullptr), last(nullptr), num_nodes(0) {

// primer-spec-highlight-start

check_invariants(); // ensure our list is set up

// primer-spec-highlight-end

}

//EFFECTS: inserts datum into the front of the list

void push_front(const T &datum) {

// A bunch of complicated code that rearranges

// pointers to add a node to the list

// ...

// primer-spec-highlight-start

check_invariants(); // make sure we didn't screw up the pointers

// primer-spec-highlight-end

}

};

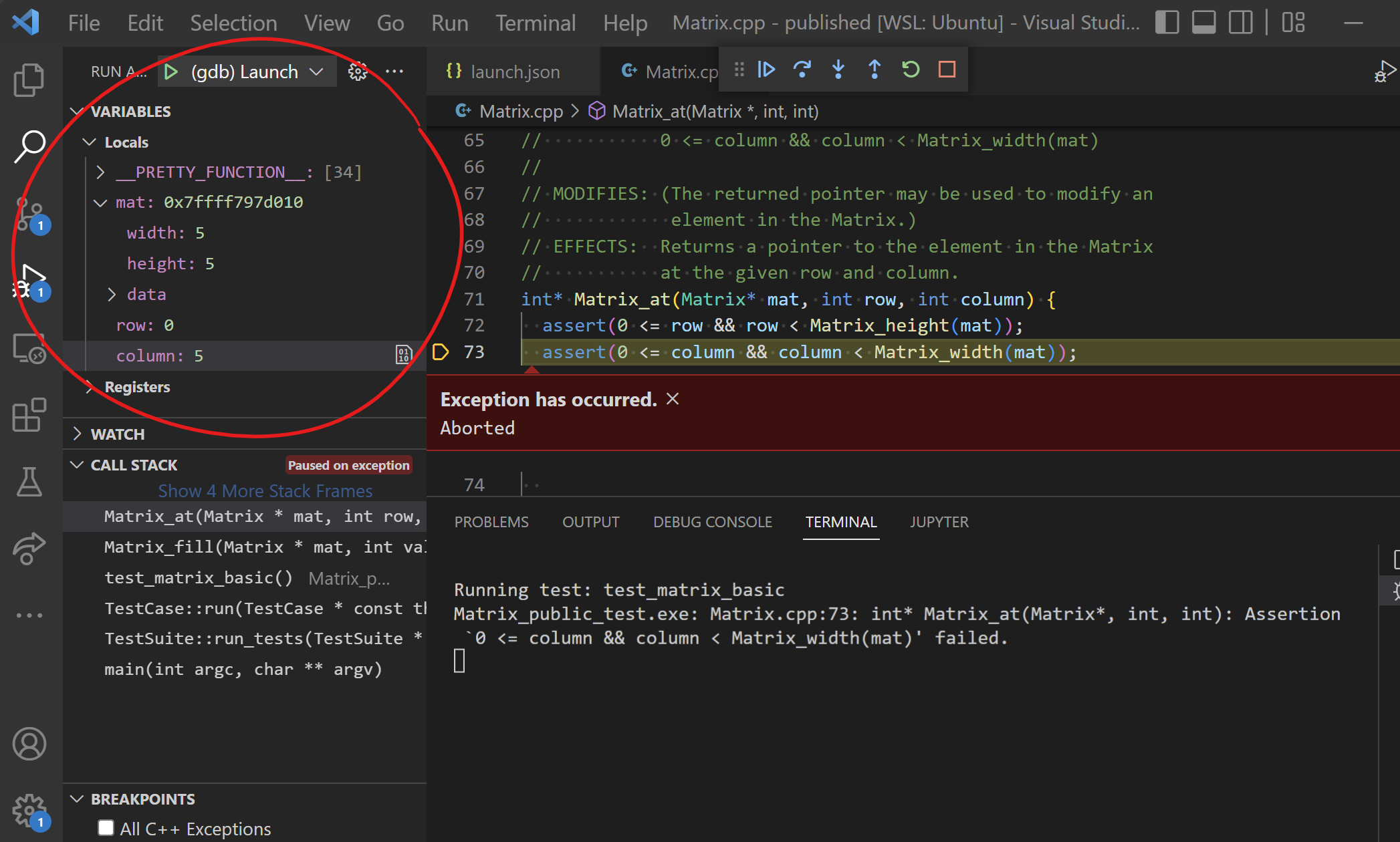

Debug Failed Assertions

Let’s say you’re running Image_public_test.exe on project 2 and

one of your Matrix_at() assertions fails:

$ ./Image_public_tests

Running test: test_image_basic

Image_public_test.exe: Matrix.cpp:72: int* Matrix_at(Matrix*, int, int): Assertion `0 <= row && row < Matrix_height(mat)' failed.

Aborted

That’s nice, but just a line number (i.e. Matrix.cpp:72) doesn’t really give us much to go on:

We need more information. Let’s run the code in our visual debugger instead. (You don’t need to add breakpoints, just run it.)

It should pause when the assert fails so that we can inspect the state of the program and figure out why the assertion is failing. First, check the local variables:

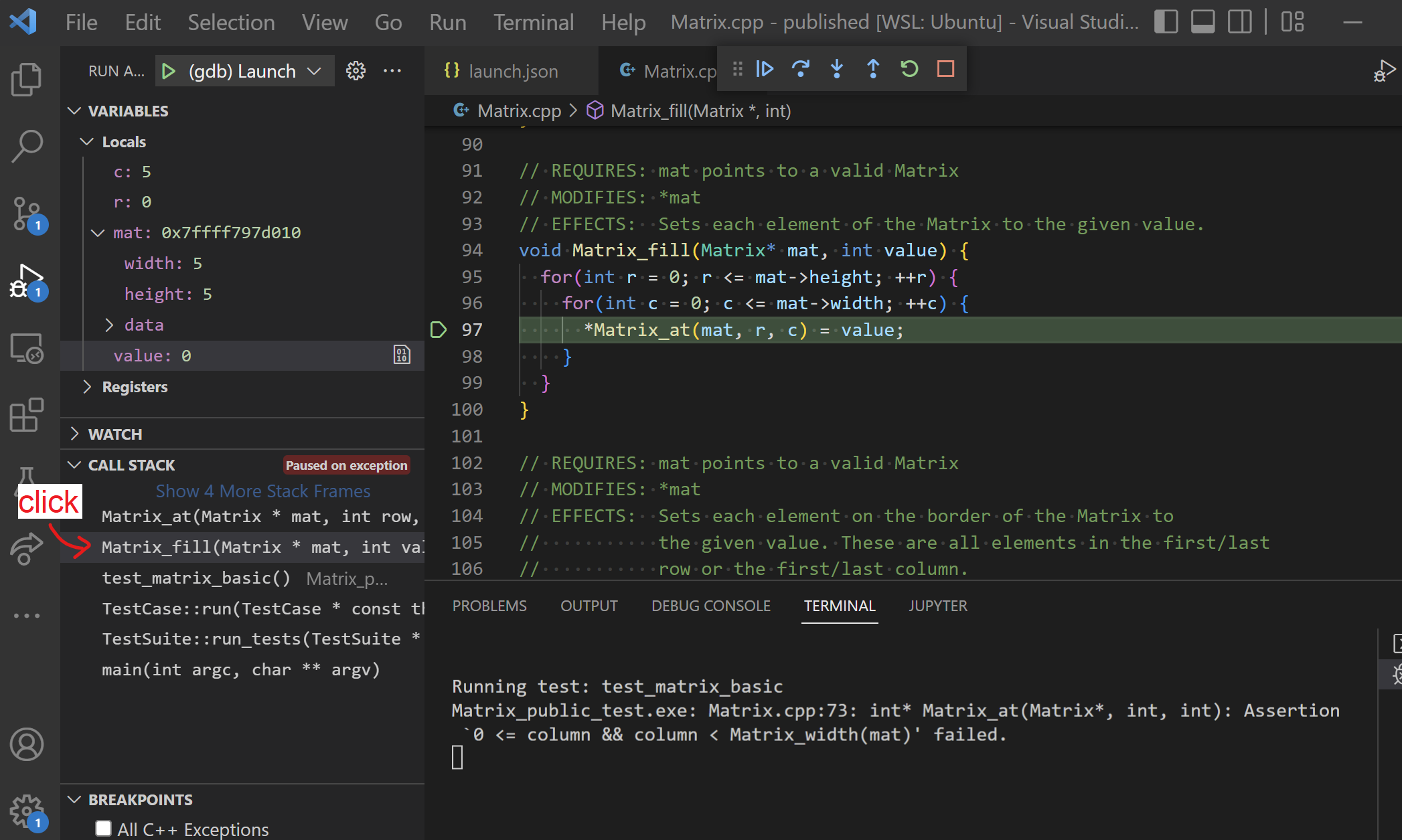

It looks like the problem is that the column parameter is too large (given width 5, only 0-4 column indices are allowed). We can figure out where this is coming from by clicking on the the stack frame for the calling context, which is the Matrix_fill() function:

Now we can actually see the call to Matrix_at() that broke its REQUIRES clause. In this implementation of Matrix_fill(), the c variable is allowed to reach value 5, which is one too large. We need to adjust the conditions on the loops to fix this.

Because we had assertions in Matrix_at(), it warned us right away that Matrix_fill() was up to no good!

Assertions for Testing

In this guide, we discuss assertions as a preemptive debugging tool. Assertions are also frequently used for unit testing, often in combination with a unit-testing framework such as the one we provide in EECS 280 that may provide additional constructs like ASSERT_TRUE or ASSERT_EQUAL(). We don’t address that context in this guide, and we don’t recommend mixing those special testing assertions into your code for debugging purposes.

Acknowledgments

Original document written by James Juett jjuett@umich.edu.

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License. You’re free to copy and share this document, but not to sell it. You may not share source code provided with this document.